More Animal-eating Plants*

As I've mentioned here before, Charles Darwin once said that he cared “more about Drosera than the origin of all the species in the world”. Drosera is the scientific name for sundew, one of the animal-eating plants, and Darwin was writing to a colleague about his major work on carnivorous plants.

As it happens, Australia has more sundew species than anywhere else in the world – 100 of the 170 species. You can see some in the Connections Garden here at Mount Annan Botanic Garden [*these notes are from the third of four interviews from Mount Annan].

The sundews (Drosera) are called ‘active’ carnivorous plants because they respond to the victim, albeit slowly. The upper surface of the Sundew’s leaf is covered with sticky tentacles, looking a bit like a sea anemone. When an insect lands on the leaf, it gets glued to the leaf by a sticky fluid secreted from a small gland at the end of the tentacle.

When the insect struggles, the tentacles close around it. The tentacles release further chemicals to kill the insect and then enzymes to digest it. There are another carnivorous plants in Australia, most of them digesting small insects to get their food.

The most striking of these are the Pitcher Plants. They grow mostly in the tropics and we have only four species in Australia: three Nepenthes (there are more than 85 species in this genus, most of them in Asia), and the unrelated Albany Pitcher Plant (Cephalotus follicularis, the only species in this genus) from streams south-west Western Australia.

These plants have leaves that produce water carrying vases or pitchers at their ends. As you might have heard me mention before, the biggest pitchers in the world are up to 30 cm (a foot) long and hold around 2.5 litres of liquid. They can digest frogs, mice and even small rats, but would still mostly live on hapless insects.

Usually an insect is attracted by sweet nectar just inside the rim and slips into a soup of digesting liquid. The ‘lid’ is there to stop too much rainwater diluting the digestive solution, not to close the trap. The insects try to escape by slippery sides and strategic ridges block their progress. (The pitcher plants are therefore described as passive, rather than active, carnivorous plants.) A forensic scientist would no doubt find that most insects die by drowning, before being slowly digested by enzymes produced by the plant and cooperative bacteria. Very similar to animal digestion.

Pitcher plants are well adapted to nutrient-poor soils in moist areas, and that’s where you find them throughout tropical Asia.

Each pitcher is a tiny ecosystem – a kind of island – biologists studying them as a microcosm of bigger world. A self contained ecosystem – bacteria, algae, insects (some dead, and some alive and predating, such as fly larvae).

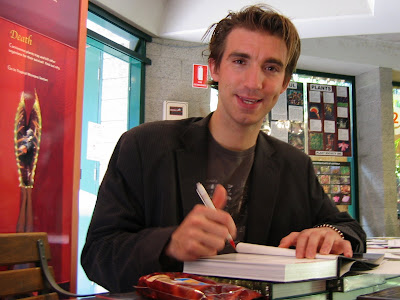

We are still finding new species of pitcher plant. Just recently a larger one was found in the Philippines - I reported on it briefly in a previous post. It was discovered by Missionaries in 2000, when they got lost for 13 days trying to climb Mount Victoria and noticed it on the way back. In 2007 Stewart McPherson (who’s written some beautiful books on carnivorous plants and is now President of the Carnivorous Plant Society of Australia) went in search of it.

It was described earlier this year (2009) and named after broadcaster and natural historian Sir David Attenborough: Nepenthes attenboroughii.

It was only in 2006 that the last of our three Australian Nepenthes species was described. We have Nepenthes mirabilis scattered around Cape York, Nepenthes rowanae from swamps near the Jardine River (also on the Cape), and the new one, Nepenthes tenax, on sand or peat in lower parts of the same Jardine River swamps.

What sets this new species apart is its rigidity and stability. The tendril that connects the pitcher to the flattened part of the leaf in Nepenthes tenax has a tight curl in the middle. This curl isn’t use for gripping nearby plants but is highly tensile and holds the pitchers erect. The name ‘tenax’ means tenacious, and refers to its ability to survive in areas exposed to strong winds.

Its stems and pitchers can stand upright without the support of surrounding vegetation. Nearly all other Nepenthes plants, with the exception of one species in Madagascar, need support and tend to grow in protected areas.

Before you start bragging about our rugged Aussie plants, I should note that the pitchers are some of the smaller in the genus, mostly only an inch or so high.

Images: Stewart McPherson signing one of his books at the Australian Carnivorous Plant Society show held at the Royal Botanic Gardens in 2008, and a line of pitchers on a Nepenthes displayed at that show.

*This Passion for Plants posting will also appear on the ABC Sydney website (possibly under 'gardening'), and is the gist of my 702AM radio interview with Simon Marnie on Saturday morning, between 9-10 am.

*This Passion for Plants posting will also appear on the ABC Sydney website (possibly under 'gardening'), and is the gist of my 702AM radio interview with Simon Marnie on Saturday morning, between 9-10 am.

Comments